Google’s search choice screen had virtually no effect on search market share, perhaps by design

Auction participants say the model favors ad-heavy search engines and redirects their profits to Google.

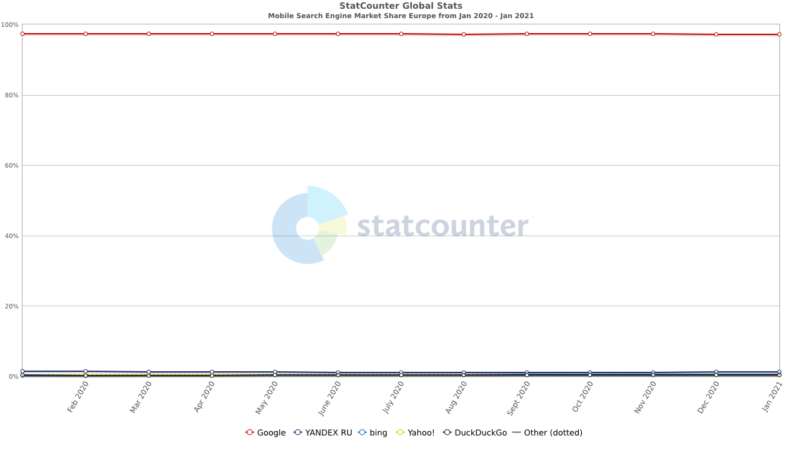

Looking at a chart of mobile search market share in Europe, you wouldn’t be able to tell that the sector is any more competitive now than it was before Google launched the search choice screen.

Source: StatCounter Global Stats – Search Engine Market Share

In February 2020, prior to the rollout, Google’s mobile search market share was 97.38%, according to statcounter. Between then and January 2021, it hovered between 97.41% (March 2020) and 97.16% (January 2021). As an antitrust remedy, the choice screen has not only failed to make the search market a more competitive space, it may even be reinforcing Google’s dominant position.

What the search choice screen is and how it came to be

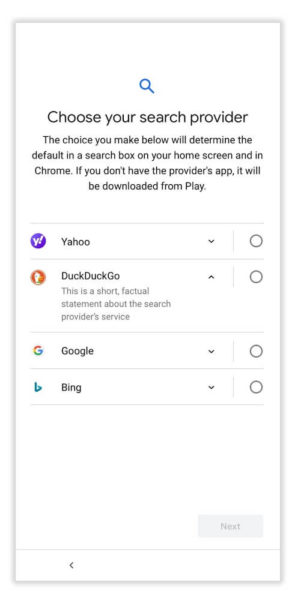

The search choice screen is a screen presented to Android users in the EU setting up their devices for the first time (or after performing a factory reset). There are four search engines (including Google) to select from, and the user’s selection determines the default search box on their home screen and in Google Chrome.

The search engine options vary from market to market (except for Google, which always appears), and are determined by a quarterly auction, in which the winners pay a fee to Google each time a user selects their search engine.

The choice screen was announced in August 2019 as part of the company’s effort to comply with the European Commission’s July 2018 antitrust ruling involving Android and app bundling. And, Google officially rolled out the screen to European users beginning on March 1, 2020.

The smartphone manufacturing process typically would have resulted in a slow rollout, but the coronavirus pandemic also disrupted mobile phone supply chains and retail sales, further delaying the choice screen’s initial impact on the mobile search market in the EU.

Experiences are mixed, but mostly negative

Now that the screen, and the auction that powers it, has been around for nearly a year, search engines have had more time to evaluate whether it has actually increased competition among them.

“The first set [of auctions] was actually worse than our expectations because nothing happened,” Gabriel Weinberg, CEO of DuckDuckGo, told Search Engine Land when asked about whether appearing as an option in Google’s search choice screen helped DuckDuckGo acquire more users. The privacy-focused search engine won spots in all EU markets during the first two auctions (March–June, and July–September 2020).

Russia-based search engine Yandex has been a winner in numerous markets since the search choice screen launched. It did not respond to our questions regarding what benefits it saw from winning spots in those markets. Instead, the company’s press service offered the following statement: “We don’t think that the current EU solution fully ensures freedom of choice for users, by only covering devices released from March 2020. There are currently very few such devices on the EU market in comparison with the total number of devices in users’ hands.”

Berlin-based non-profit search engine Ecosia, which initially boycotted the auction, did eventually participate. It won a slot in a single market each of the two times it participated, although it did place bids in multiple markets. “We have seen no effect on our user numbers, given we only won a slot in the one small market each time,” said Sophie Dembinski, head of public policy at Ecosia, adding that, “Our core mission is to fight climate change by planting more trees in areas affected by deforestation. Being pulled into an expensive and counterproductive bidding war such as the Android auction takes away from that mission.”

One company, however, responded to our inquiries with neutral, if not positive, comments: Info.com, which is owned by American company System1, has consistently appeared as an option in all 31 EU territories since March 2020. Although it did not answer questions regarding the impact the search choice screen has had on its business, it did provide a statement from System1 President Paul Filsinger: “System1 has no complaints. We believe the current Android Choice Screen auction rules have been fairly implemented and the current process offers consumers clear alternatives for their default Android search engine.”

Bing, which leads the competition among non-Google search engines, was curiously absent from the screen during the first two auctions, winning only one spot in the UK when the screen first launched. In Q4 2020, it did, however, win in 13 markets, and in Q1 2021, it appeared in 11 markets. It declined to comment for this article.

Why the choice screen hasn’t improved competition

The search engines that spoke to us cited the auction model, the implementation of the screen itself and its limited availability as the main factors preventing Google’s solution from improving competition in the mobile search sector.

The auction model. When it was announced, the auction aspect of the search choice screen raised eyebrows. Now that search engines have experienced it in practice, it has become a point of contention.

“Alternative search engines are finding it harder than ever to compete against Google,” Ecosia’s Dembinski said, “If they are fortunate enough to ‘win’ an Android auction, they now find unnecessary costs added to their business.”

DuckDuckGo also applied quotation marks to the term “win”: “If you ‘win,’ you’re not really a winner, because you’re giving all of your profits directly to Google, which just seems like it undermines the entire point of a thing that’s supposed to increase competition in the search market,” Weinberg said.

DuckDuckGo, which has steadily gained traction among privacy-minded users, recently exceeded 100 million searches in a single day. That’s a far cry from the billions of searches that Google serves, but search engines like DuckDuckGo and Ecosia have been able to attract users by differentiating themselves from the industry leader. Instead of attempting to challenge Google directly, they’re seeking out underserved audiences and crafting their business models to fit their needs.

Collectively, these alternative search engines can chip away at Google’s dominance, but what makes them appealing to users may also be holding them back when it comes to the search choice auction. “People want us for privacy and it does mean that we make less per user, but that also means we can’t get on the screen in this format,” Weinberg said. Ecosia, which directs all of its profits towards climate action, faces a similar situation because it can’t afford to bid as high as a for-profit search engine might.

“Slots tend to be allocated to for-profit enterprises with significant financial backing, rather than those that are high quality and popular with users,” Dembinski said. Search engines typically generate revenue by showing ads, and they can bring in more revenue by tracking users to enable targeted advertising, displaying a greater volume of ads or, in the case of non-profits, scaling back on donations. Among users, these are largely unpopular practices, and in the case of showing more ads, may also diminish the user experience. Bringing in more profit does, however enable search engines to bid higher and potentially win spots on the search choice screen.

Whether intentionally or not, the auction model has created a system in which search engines are encouraged to prioritize profits so that they can pay a portion of those profits back to Google for the privilege of appearing on the screen, alongside Google. The focus on profits may mean that search engines have to sacrifice user experience or make other strategic decisions that would be unpopular with their target audiences.

As the host of the auction, Google doesn’t have to bid and is insulated from these considerations. This may be creating a situation in which the options that appear on the search choice screen present ad-heavy experiences that only make Google look more attractive by comparison.

Bing is also a leading search engine, and is likely to have the resources to win in all EU territories if it so desired. However, in Q1 2021, it only appears in 11 (out of 31) territories, a rather low percentage for the world’s second most popular search provider. Bing’s inclusion on the screen might seem like an obvious choice from a user’s perspective, but this may be a case in which its success is a double-edged sword: under the current auction model, popular search engines (other than Google), may be paying for users that would’ve selected them as their default search provider even if they didn’t appear on the screen. In this manner, the auction model is able to extract revenue from both larger and niche Google competitors.

The screen itself. Google’s way of presenting search providers to users also presents problems. Since there are only four slots, including Google, users are made to manually install their preferred search engine if it doesn’t appear among the options. Additionally, Google does not tell users how it determines which options to show during the setup process. In the minds of users, this may delegitimize the search engines that don’t appear on the choice screen.

Returning to the choice screen is unlikely, since it only appears once per device, during the setup process, meaning that the user would have to perform a factory reset to get back to it. Once a user makes a selection, they’re essentially stuck with it, unless they manually re-assign their default search provider, which takes 15+ presses, according to DuckDuckGo. And, many users may not be familiar enough with Android’s menus to ever go through the trouble of switching.

The distribution method. As Yandex said above, the screen only appears on devices released after March 2020, and that may be a small percentage of devices compared to the total number of Android devices currently in active use.

“The way Google has rolled this out is OEMs [original equipment manufacturers] have to submit new builds that have to get approved,” DuckDuckGo’s Weinberg said, “And then the pandemic slowed that down even more, but even without the pandemic it was going to go super slow, I think by design.” The limited availability of the choice screen, whether due to the pandemic, the build approval process or both, means that many Android users are not being asked to select a default search provider, which typically means that Google retains its position as their default search engine.

Google’s response. When asked for comment regarding the points above, a Google spokesperson told Search Engine Land:

“Android provides people with unprecedented choice in deciding which applications they install, use and set as default on their devices and research shows that Europeans understand how to switch search engines should they wish. The choice screen provides people with even more choice and we’re always happy to discuss feedback with the European Commission.”

The choice screen needs to improve

The search choice screen and auction model may present users with a choice that wasn’t really there before, but competitors are far from being on equal footing with Google. And, an uneven playing field means that businesses are susceptible to any algorithm changes or strategic decisions Google makes.

The auction itself discriminates against certain business models that clearly have an audience, and thus may be nudging those audiences towards Google. It is also based on an artificial scarcity: There does not seem to be a practical reason for limiting the options to four. While it does create a more simplistic menu for users, users may also benefit from an alphabetized, searchable drop-down menu in addition to the four main options.

Since options are so limited and are only based on what a search engine is willing to pay per user, Google could streamline its process of assigning a different search engine as the default on Chrome and the home screen search box. Instead of making it a multi-step process involving manually downloading the app, adding the corresponding widget and sorting through the settings menu to assign defaults, Android could automate these disparate tasks upon downloading a search app or in a single, dedicated menu.

More competition among search engines may mean that marketers have to divide their attention or specialize, but that would also mean that our success isn’t entirely contingent upon one platform and the decision-makers that control it. A new search choice screen could decrease Google’s mobile share as much as 20% in certain markets. If that figure seems high, that’s because it is, but under the current scheme, Google’s share of the mobile search market has only declined fractions of a percentage point, suggesting that the choice screen has had little, if any, effect on the competitive landscape.